A diet for life

What disease affects 33% of Canada’s population, and costs the health care system $6 billion per year? Obesity, spreading rapidly around the world, doubles in prevalence every five years. Clearly an epidemic.

In the U.S., 1995 marked a milestone, when the prevalence of overweight in adults reached 50%. And this even though people are eating less fat. Surprisingly, low-fat eating may be causing more obesity!

Clearly, not everyone becomes obese. Is it entirely a question of how many calories you eat, or how much exercise you get? Highly unlikely; these factors are probably less important than genetic makeup and what a person eats.

Let’s first discuss genetics. The so-called “thrifty gene”is found in about 25% of the North American population, and a much higher percentage of aboriginals. People with this “thrifty gene” often become obese and develop adult-onset diabetes, along with cardiovascular disease, high blood pressure, and so on, when eating a typical North American diet. In the case of aboriginal peoples on traditional diets, these illnesses were essentially unknown. What changed?

One hypothesis is that thrifty gene carriers have a metabolism genetically programmed for a “hunter-gatherer” diet. In a typical hunter-gatherer society, game or fish providing fat and protein is supplemented by edible leaves, flowers, roots, tubers, and insects. Much of the carbohydrate in these foods could not be absorbed, either because it was indigestible fibre or because modern cooking and processing methods had not been invented. Moreover, these primitive foods had not yet undergone selective breeding to increase sugar and starch content to the levels of modern-day fruits and vegetables. Thus, hunter-gatherers subsisted on low-carbohydrate diets.

However, once every year, in autumn, the availability of high-carbohydrate items would increase dramatically, as wild fruits, nuts, and vegetables ripened. Hunter-gatherers who feasted during this period, and were thus able to accumulate lots of body fat, would be better able to survive the winter, during which all types of foods would be either scarce or difficult to find or hunt, or both.

Obviously, individuals having a genetic endowment of the ability to get fat easily on a high-carbohydrate diet, were more likely to survive and pass their “thrifty gene” on to their offspring.

At some point in prehistory, however, some cultures began to deliberately grow foods for consumption. This agrarian revolution had far-reaching effects: permanent settlements; the invention of currency, and a change of diet. Grains can be stored all year round, thus providing a continually available high-carbohydrate food source. As a result, the hunter-gatherer metabolism became unsatisfactory and had to evolve; after all, if you can put on weight quickly on a high-carbohydrate diet, you will rapidly become obese if you eat high-carbohydrate grains all year round. Obese people die early of all sorts of diseases, and reproduce less; over time, the “thrifty gene” responsible for obesity would be less prevalent. Thus we arrive in the twentieth century, where about 75% of the overall population no longer has this thrifty gene, and can tolerate high-carbohydrate diets year-round without gaining excessive weight.

Why do individuals with the thrifty gene become obese on high-carbohydrate diets? Let’s consider energy metabolism. Carbohydrates consist of sugar molecules; when eaten, blood sugar levels go up, signalling the pancreas to secrete insulin. The insulin in turn signals fat and muscle cells in the body to take up sugar from the bloodstream. Muscle cells store the most important of these sugars, glucose, as glycogen, but fat cells turn it into fat. No insulin, no fat storage. In fact, fat cells are continuously breaking down fat, and in the absence of insulin, this fat provides energy for many body organs. Thus, without insulin, a person would lose weight, which is what happens in untreated juvenile-onset diabetes.

Persons with the thrifty gene have an exaggerated insulin response to blood sugar levels. Their pancreases secrete more insulin for a given level of blood sugar, and thus fat cells are rendered more efficient at storing blood sugar as fat. For this reason, a person with the thrifty gene, eating the same high-carbohydrate diet as someone without the thrifty gene, will put on weight more quickly. If he or she continues on such a high-carbohydrate diet, their insulin levels will be high, i.e. they will have “hyperinsulinemia”.

Another effect of high rates of insulin secretion in response to high-carbohydrate meals is a rapid and pronounced drop in blood sugar levels, possibly to values even lower than before eating. In some individuals, these sharp decreases in blood sugar trigger the adrenal glands to secrete hormones responsible for the “fight or flight” response to stress. This stress response may be experienced as anxiety. Together with low blood sugar levels producing lightheadedness and tremulousness, these are the symptoms of reactive hypoglycemia.

Hyperinsulinemia will not cause weight gain indefinitely. At some point, high insulin levels and overweight cause fat cells to begin to ignore insulin, a condition called “insulin resistance”. One consequence is reduced weight gain, which is good. However, sugar levels in the bloodstream will climb and when high enough, sugar will spill into the urine, a condition called diabetes mellitus. Diabetics urinate a lot, and therefore need to drink a lot. What’s worse, they get heart disease, kidney problems, retinal changes which can cause blindness, as well as neurological abnormalities.

Professor Walter Willett of Harvard University’s School of Public Health, in a recent interview with the French magazine “Sciences & Avenir” revealed the latest, as yet unpublished, findings of the extremely large epidemiologic study ongoing since 1976 at Harvard. Over 65,000 women and 42,000 men were followed for 6 years, during which time 915 cases of non-insulin-dependent diabetes developed among the women and 523 cases in the men. They found that the risk of developing diabetes was increased by 50% for those that consumed high quantities of readily absorbed carbohydrates such as white bread, boiled or mashed potatoes, breakfast cereals, or jam. If they also had diets low in fibre, their risk for diabetes was more than doubled.

The above suggests that the low-fat, high-carbohydrate diet advocated by nutritionists, dieticians, cardiologists, fitness experts, et al, rather than reducing overweight, can cause it in one-quarter of North Americans, and is thus partially responsible for the current epidemic of obesity and adult-onset diabetes.

I believe that these experts are misguided when they want to apply a diet suitable for the three-quarters of the population with an agrarian type of metabolism, to the other one-quarter who carry the thrifty gene of hunter-gatherers. The food industry, which profits from adding sugar and starch to their products, support these experts.

My research and my personal experience both suggest that it is possible for individuals with a thrifty gene to prevent the development of obesity and its attendant illnesses, including diabetes and heart disease, by following a low-carbohydrate diet, high in fat and/or protein; high fat in particular causes many weight-conscious people to panic. We all know that fat contains 9 calories per gram, versus only 4 calories for carbohydrates or proteins. So won’t eating fats cause rapid weight gain?

Yes, but only if there are appreciable insulin levels in the blood when dietary fat is being absorbed, which occurs when carbohydrates are eaten along with the fat. Most truly fattening foods are high in both fats and carbohydrates: snacks like potato chips or chocolate bars, rich desserts like cheesecake or ice cream, and fast foods including hamburgers and french fries. These foods guarantee weight gain for people with the thrifty gene. Are you among the 75% who can safely eat these foods, or the other 25% who must avoid them? How can you tell which group you belong to?

Some markers of the thrifty gene are: a tendency to obesity, particularly so-called “central obesity” in which fat builds up around the waist; adult-onset diabetes associated with obesity; gestational diabetes (ie diabetes occurring during pregnancy); reactive hypoglycemia; having a strong family history of these conditions; or being a North American aboriginal. It is possible that some individuals have a metabolism falling between the hunter-gatherer and agrarian types. Little information exists about an optimal diet for these people.

If you believe that you carry the thrifty gene, what can you do to prevent or reverse obesity and diabetes?

Dr. Atkins, a U.S. cardiologist, has published a number of books on low-carbohydrate eating; his latest is “Dr. Atkins’ New Diet Revolution”. Besides his extensive clinical experience, the book includes recipes and carbohydrate charts. Other clinicians have also written practical books about low-carbohydrate eating. One caution: read the entire book before starting, and don’t begin partially by replacing some carbohydrates with fat. This is certain to make you gain weight!

Low-carbohydrate eating requires commitment to a lifestyle change. Once you’ve taken the plunge, however, it’s easy to stick with. After all, you can eat as much as you want, of foods made tasty by fat. Fat suppresses appetite, and carbohydrate cravings often disappear entirely, as do indigestion and bloating after carbohydrate-rich meals. The diet “cures” diseases caused by carbohydrates, such as lactose or gluten intolerance. And a very-low-carbohydrate “ketogenic diet” is an effective treatment for many children with epilepsy. Recent reports suggest that higher fat intakes reduce stroke risk also.

Let me tell you about my personal experience with low-carbohydrate eating. Overweight and unathletic from childhood, I resolved after my first child arrived to improve my health. Stopping smoking led to a ten pound weight gain, even though I cycled to work daily. I chanced upon Dr. Atkins’ diet, and with it easily lost 20 pounds , dropping to 150 pounds on my 5 foot 9 inch frame. When I stopped the diet, I rapidly gained 5 pounds (probably due to water retention, more bulk in my colon, and more glycogen stores in my muscles). Over the next 25 years, my weight crept up to 175 pounds, in spite of taking up running, cross-country skiing, roller-blading, and triathlons.

My wife and I both have strong family histories of diabetes and heart disease, and so in October 1996 we agreed to go on the Atkins diet. I lost 12 pounds in 6 weeks, and I have kept my weight steady by avoiding potatoes, rice, bread, pasta, and sugar except for special occasions; we eat a lot of meat, cheese, fish, and eggs, and some high-fibre vegetables daily, particularly lettuce, celery, raw spinach, peas, green beans or broccoli. Fruit juices are out, although we have desserts of raw fruit occasionally. Large dollops of mayonnaise accompany meats, we fry foods in canola oil, and added butter makes cooked vegetables tasty. A typical breakfast is 5 strips of bacon and 3 fried eggs with pan drippings. A heaping tablespoon of psyllium husks in a large glass of water prevents constipation. We supplement our diet with a multivitamin tablet, 1000 mg of slow-release vitamin C, 800 IU of vitamin E, beta-carotene, a calcium and magnesium tablet, and a garlic capsule, daily. I enjoy coffee (no sugar!) with 35% cream. For snacks, a handful of nuts, celery sticks with cream cheese or peanut butter, or cold cuts with mayonnaise hit the spot. A glass of red wine accompanies supper.

Reading labels carefully when shopping is essential. We avoid all “lite” or “low-fat” foods, or items containing sugar in various forms (glucose, sucrose, dextrose, maltodextrin, corn syrup or solids, fructose, etc.). When carbohydrate content is indicated, we aim for a gram or less per serving.

Some nutrition knowledge helps, for instance in avoiding foods with a high “glycemic index”, such as sugar or white bread; these foods raise blood sugar levels, and therefore insulin levels, the highest. Those with a low glycemic index (usually foods with high fibre content, little processing, or containing amylose starch which is digested more slowly than amylopectin) can be eaten in small quantities. Canola and olive oil are both high in monounsaturated fatty acids, believed to improve cholesterol profiles. High-amylose diets can reduce blood triglyceride levels.

On the diet, we no longer experience bloating or gas after meals. My endurance when running, cycling, or cross-country skiing has improved. Because I burn fats instead of glycogen when exercising, I no longer “run into the wall” or “bonk” when my muscles run out of glycogen. Eating lunch after a distance run used to cause hypoglycemic symptoms in the afternoon; these have disappeared.

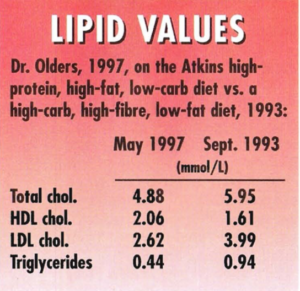

Friends are horrified when I tell them about the diet. “Aren’t you worried about your cholesterol, eating all those eggs and saturated fats?” As a physician, I was worried also, so I had my cholesterol tested after seven months on the diet. A family doctor colleague was incredulous when he saw the results: “I’ve never seen such a high HDL level for a male!” The table compares my lipid profile on the diet with an earlier test while eating high-carb, high-fibre, low-fat. All values are in mmol/L.

A middle-aged friend who started the diet to control diabetes and lose weight, lost 30 pounds in three months, was able to discontinue her two anti-diabetes medications, and looks and feels great! She plans to eat low-carb for life.

A middle-aged friend who started the diet to control diabetes and lose weight, lost 30 pounds in three months, was able to discontinue her two anti-diabetes medications, and looks and feels great! She plans to eat low-carb for life.

Please note that low-carb is not for everyone; it might even harm those lacking the thrifty gene. And I have concerns about the possible cancer-causing potential of fried and grilled animal fats. My doctor friends worry about the ketotic state caused by a very low carbohydrate intake. I remind them that the Inuit do very well on their traditional diet which essentially excludes carbohydrates for most of the year.

Many women, especially, have been led to believe that high fat consumption increases risk of breast cancer. Apparently not so: Dr. Willett from Harvard also lays this myth to rest with a study recently published in the Journal of the American Medical Association. There were 2956 women out of almost 89,000 who developed breast cancer during 14 years of followup in the Nurses’ Health Study. The risk of developing breast cancer was lower for those women with higher proportion of energy intake from dietary fat.

I believe that low-carb eating is gradually gaining acceptance; cookbooks are starting to appear, and we can hope that farmers will return to growing high-fibre, low-starch and low-sugar produce. The dangers of low-fat are beginning to be recognized, and the obvious benefits of low-carb for obese diabetics will eventually win over even the sceptics, both patients and doctors.